via Resources

DEBATERS

Jamil Zaki, an assistant professor of psychology at Stanford University, is the lab director of the Stanford Social Neuroscience Laboratory and founder of The People’s Science. He is on Twitter(@zakijam).

Paul Bloom, the Brooks and Suzanne Ragen Professor of Psychology and Cognitive Science at Yale University, is the author, most recently, of “Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion.” He is on Twitter(@paulbloomatyale).

Empathy Can Lead to Short-Sighted and Unfair Moral Bias

What does it take to be a good person? What makes someone a good doctor, therapist or parent? What guides policy-makers to make wise and moral decisions?

What does it take to be a good person? What makes someone a good doctor, therapist or parent? What guides policy-makers to make wise and moral decisions?

Many believe that empathy — the capacity to experience the feelings of others, and particularly others’ suffering — is essential to all of these roles. I argue that this is a mistake, often a tragic one.

Empathy acts like a spotlight, focusing one’s attention on a single individual in the here and now. This can have positive effects, but it can also lead to short-sighted and unfair moral actions. And it is subject to bias — both laboratory studies and anecdotal experiences show that empathy flows most for those who look like us, who are attractive and who are non-threatening and familiar.

Empathy has its place but reason should guide action, as it aspires toward the sort of fairness and impartiality empathy doesn’t provide.

When we appreciate that skin color does not determine who we should care about, for example, or that a crisis such as climate change has great significance — even though it is an abstract threat — we are transcending empathy. A good policy maker makes decisions using reason, aspiring toward the sort of fairness and impartiality empathy doesn’t provide.

Empathy isn’t just a reflex, of course. We can choose to empathize and stir empathy for others. But this flexibility can be a curse. Our empathy can be exploited by others, as when cynical politicians tell stories of victims of rape or assault and use our empathy for these victims to stoke hatred against vulnerable groups, such as undocumented immigrants.

For those in the helping professions, compassion and understanding are critically important. But not empathy — feeling the suffering of others too acutely leads to exhaustion, burnout and ineffective work. No good therapist is awash with anxiety when working with an anxious patient. Some distance is required. The essayist Leslie Jamison has a great description of this, in writing about a good doctor who helped her: “His calmness didn’t make me feel abandoned, it made me feel secure,” she wrote. “I wanted to look at him and see the opposite of my fear, not its echo.”

Or consider a parent dealing with a teenager who is panicked because she left her homework to the last minute. It’s hardly good parenting to panic along with her. Good parents care for their children and understand them, but don’t necessarily absorb their suffering.

Rationality alone isn’t enough to be a good person; you also need some sort of motivation. But compassion — caring for others without feeling their pain — does the trick quite nicely. Empathy and compassion are distinct: Recent neuroscience studies, including some fascinating work on the power of meditation, show that compassion is distinct from empathy, with all its benefits and few of its costs.

Many of life’s deepest pleasures, such as engagement with novels, movies and television, require empathic connection. Empathy has its place. But when it comes to being a good person, there are better alternatives.

Moral Wisdom Requires Empathy

Paul, you aptly point out the perils of relying on empathy. But you also overstate its problems and undersell its importance.

Paul, you aptly point out the perils of relying on empathy. But you also overstate its problems and undersell its importance.

For one thing, you are sparring against a straw version of “empathy.” Encountering an upset friend, one might vicariously share his feelings, understand where those feelings come from and wish for him to feel better. All of these experiences are pieces of empathy, but you have thinned out the definition to only include its emotion-sharing component. This is like arguing that European food isn’t delicious, but first defining “European food” strictly as haggis.

You also describe emotions as volatile and irrational. This perspective is dated, harkening back to the Greek notion that people must subdue their passions through reason, like a rider on a wild horse. But in fact people work with, not against, their feelings, turning them up or down to suit their needs. Empathy is no different. Yes, it’s an emotional spotlight, but people have the ability to point this spotlight as they see fit. My own research demonstrates that when people simply believe empathy is under their control, they are inspired to try harder at it — for example, in paying attention to the emotions of people who differ from them ethically or politically.

Enshrining pure logic to guide morality is naïve. Even when people try to be objective, they often confirm what they want to believe.

Why bother working with empathy if we can better ourselves through principle alone, as you argue? Because empathy makes a difference — not always, but more than you suggest. It helps to receive empathy. For example, cancer patients experience less depression and more empowerment when their physicians express empathy. It also helps to give it: People who behave kindly grow happier and healthier, most of all when they act out of empathy.

Those who choose empathy grow a broader, richer emotional life.

And it helps to be around it, because empathy, even toward one person, can jumpstart human care for larger groups. Many Americans opposed slavery before 1852, but “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” in shedding light on its horrors, moved millions and sparked a new momentum for abolitionism. In cases like this, empathy enlivens moral principles, making them urgent.

Of course, Paul, you’re right that people do dole out empathy lazily — to others who look or think like them — or cynically, to spark aggression. But enshrining pure logic to guide morality is naïve. Even when people try to be objective, they often confirm what they want to believe. In our post-truth world, people can use reason like a shield, curling up in comfortable assumptions, surrounding themselves with others who amplify their biases. If people don’t want to broaden their empathy, they’ll probably use reason narrowly as well.

No piece of human psychology is always good or bad, and arguing for or against empathy makes no more sense than arguing for memory or against attention. Instead, we should motivate people to align empathy with their sense of what is right.

Moral wisdom requires bringing together the force of emotion and the precision of principle, not splitting them apart.

There Is a Difference Between Empathy and Compassion

Jamil, I worry about your lumping together some very different psychological processes — such as feeling, understanding and motivation — when you talk about “empathy.” For one thing, it means we’re talking past each other. To use your analogy, it’s as if I wrote a book “Against Haggis” and you responded by citing papers showing how Scottish salmon is good for the heart.

Jamil, I worry about your lumping together some very different psychological processes — such as feeling, understanding and motivation — when you talk about “empathy.” For one thing, it means we’re talking past each other. To use your analogy, it’s as if I wrote a book “Against Haggis” and you responded by citing papers showing how Scottish salmon is good for the heart.

My usage of the terms is pretty typical; there are many scientists and philosophers and laypeople who define “empathy” and “compassion” exactly the same way I do. More important, there are many who believe the empathy — in the sense of feeling others’ feelings — really is central to being a good person.

I believe there is a marked difference between empathy and compassion. And when you lump them together, you leave less room for the richness of moral psychology and make it harder to properly explain the phenomena you discuss.

When you lump them together, you leave less room for the richness of moral psychology and make it harder to properly explain the phenomena behind being a good person.

Exactly what was it about “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” that had such a positive social effect? Precisely what is it that doctors are doing that is making their patients less depressed? When you say humans do better when we “harness empathy,” are you talking about feeling, understanding, motivation — or some specific combination of all three?

I do agree with you that emotions have mixed effects. Lust can be terrific, but certainly not for doctors doing medical exams. Similarly, empathy can be wonderful — empathic engagement is central to the enjoyment of fiction, for instance — but it has serious design flaws, such as bias and narrowness, that render it a poor guide to being a good person. To the extent that we need an emotional push, we’re better off with compassion.

Finally, you note that humans can do poorly when it comes to reasoned deliberation. I agree — but the solution is not to listen to our hearts, to fall sway to our biases and prejudices. Rather it is to reason better, often with the help of other people, to explore arguments and counter-arguments, considering various examples and so on.

After all, isn’t this what we are doing right now?

Emotion and Reason Are Inextricably Intertwined

You accuse me of lumping, and I plead guilty. But in this case lumping is realistic, because empathy does mean more than one thing: It includes sharing, thinking about, and caring for others’ inner lives.

You accuse me of lumping, and I plead guilty. But in this case lumping is realistic, because empathy does mean more than one thing: It includes sharing, thinking about, and caring for others’ inner lives.

Scientists can differentiate between these “pieces” of empathy, for instance, because they activate different systems in the brain. But just because two things can be separated doesn’t mean they are always or even usually neatly divided. To continue our food fight: People can tell the difference between chickpeas and olive oil, but real world empathy is more like hummus — blended, often for the better.

For instance, brain systems that are involved in both sharing and thinking about emotions allow people to insightfully understand what others feel. And in psychological research, the most tried and true way to ramp one’s “compassion” is through “cognitive empathy,” i.e. by asking people to consider others’ point of view.

Compassion has strengths, and emotional empathy has weaknesses, but splitting these emotions is too simplistic.

Which piece of empathy, then, provides the best push toward goodness? It depends. Someone who has just seen a police shooting video doesn’t need another emotional punch in the gut, but could leverage his feelings to better understand the perspective of communities of color. Someone who reads devastating statistics about Yemeni refugees might also watch evocative videos of their plight, hijacking her emotional empathy to inspire action.

I agree that compassion has strengths, and emotional empathy has weaknesses. But neither is a poor guide to being a good person, and neither is a moral cure-all. This might seem lumpy to you, Paul, but splitting these emotions is too simplistic.

Emotion and reason are also intertwined. People constantly think themselves into and out of feelings. Strong emotions can act like a psychological alarm system, drawing our consciousness toward whatever causes them. In the best cases, emotions help us reason better, by forcing us to consider new points of view.

Emotion is woven into the fabric of our minds and that’s a good thing. Although feelings alone don’t make us good people, they are key ingredients in our moral lives.

Writing Assignment:

Day 1. Write a constructed response that answers the question, introduces the topic, and cites and explains.

Who makes the stronger argument?

Day 2 Thursday May 11 . Write an introductory paragraph.

Prompt:

Compose an introductory paragraph that takes a position on the following topic:

Agree or disagree–Empathy is overrated.

Your introduction must

- introduces the topic

- addresses a counterclaim

- and contains a thesis

Assignment:

Read and take notes on the article, Is It Illegal to Wear Masks at a Protest? It Depends on the Place

Read the following articles and write a introductory paragraph that:

- introduces the topic

- addresses a counterclaim

- includes a thesis statement

Write in the active voice and maintain clarity for your reader.

Additional resources:

Article–Bill to ban masks at protests

Read the following articles and write a response that:

- introduces the topic

- takes, a position

- Cites sources

- and addresses counterclaims

Write in the active voice and maintain clarity for your reader.

Writing tip:

Active voice describes a sentence where the subject performs the action.

The boy fed the dog — active

not

The dog was fed — passive

Steven Pinker on writing style:

A Man Who Spent 27 Years Alone in the Woods on the Best of Hermit Literature

At the age of 20, a highly intelligent but socially awkward young man named Christopher Knight made a radical decision to leave the rest of the world behind. He lived completely alone in a nylon tent in the woods of central Maine, remaining hidden, without having a single conversation with another human, for the next 27 years, until he was arrested in 2013 while stealing food from a summer camp.

Knight read thousands of books while living in the woods—he stole his reading material, as well as food and clothing, from the summer camp and dozens of nearby cabins. After his arrest, he was reluctant to speak about many topics, but was willing to engage in some robust literary criticism.

What does a man who may have spent as much time in total seclusion as any known person in history have to say about the masters of hermit literature?

Let’s find out.

Lao-Tzu, The Tao te Ching

The Tao te Ching is widely regarded as the first great work of hermit literature. It was written in China around the 6th century B.C. by a hermit known only as Lao-Tzu (“Old Master”). The book contains 81 short verses that extol the pleasures of forsaking society and living in harmony with the seasons.

Christopher Knight said that he felt a deep-rooted connection to the book, approving of its philosophical underpinnings. The Tao says that it is only through retreat rather than pursuit, through inaction rather than action, that one truly acquires wisdom. “Those with less become content,” it states, “those with more become confused.”

The Tao te Ching notes that “happiness rests in misery,” which explains Knight’s relationship with winter. Knight suffered in the extreme cold of Maine—he never lit a fire, for fear that smoke would give his campsite away—and yet the stillness of a hard-frozen day could also fill him with contentment.

The Tao te Ching offers insightful, if enigmatic, insights into solitude. Guessing by Knight’s statements, if he were forced to chose a score for the book on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 representing the most astounding of hermit reads, Knight might give the Tao te Ching an excellent 8.

The Essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson

“People are to be taken in very small doses,” wrote Emerson in “Society and Solitude,” published in 1857. The second-to-last line of his famous essay “Self-Reliance” reads, “Nothing can bring you peace but yourself.”

These sentiments appealed to Knight. Even more deeply, Emerson seemed to understand Knight’s need to live in the forest. We disengage from the world, Emerson wrote, to seek what he called waldeinsamkeit, which he described as the feeling of being alone in the woods “The forest is my loyal friend,” he wrote. This is exactly how Knight felt.

During Knight’s 27 years in the woods, he never once saw a doctor. He never even had a particularly bad illness. Emerson seemed to intuit how this was possible. In the woods, Emerson wrote, “a man casts off his years” and finds “perpetual youth.”

Knight’s projected score for the essays of Emerson: a solid 7.

The Poetry of Robert Frost

Don’t even mention Robert Frost to Christopher Knight. Too simplistic, too Disneyfied. Too popular.

Score: a terrible 2.

The Poetry of Emily Dickinson

For the last seventeen years of her life, Dickinson never left her home in Massachusetts and spoke to visitors only through a partly closed door. She didn’t even leave her room to attend her father’s funeral.

Knight marveled at Dickinson’s poetry, sensing her kindred spirit. “Saying nothing,” she wrote, “sometimes says the most.” Knight also appreciated that her poems were not intended for publication—writing for the outside world, according to Knight, is an egotistic act, a way of saying, “Look at me!” No real hermit would do such a thing.

Dickinson wrote solely for self-fulfillment—she composed close to 2,000 poems, yet fewer than a dozen were published during her lifetime, none with her direct authorization, and none with her name on it. “Silence is Infinity,” she wrote.

She made her younger sister, Lavinia, promise to destroy her papers upon her death. Dickinson died in 1886, at age 55, and Lavinia burned most of the poet’s correspondence, but kept her notebooks, read the verses within, and had them published.

Knight’s envisioned score: an astounding 9.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Thoreau lived in his cabin on Walden Pond in Massachusetts for two years and two months, starting in 1845. He escaped the world, reducing existence to its basic elements, to “live deep and suck out all the marrow of life,” he wrote in Walden.

“I love to be alone,” Thoreau added. “I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude.” This seems to precisely mirror Knight’s sentiments. And yet Knight despised Thoreau.

“Thoreau,” said Knight, “was a dilettante.” The great Transcendentalist was also, according to Knight, a fraud. During his retreat, Thoreau socialized frequently in the town of Concord. His mother did his laundry. One dinner party at his place numbered 20 guests.

Thoreau’s biggest sin may have been publishing Walden—packaging his thoughts into a commodity, brazenly seeking fame and fortune. Knight’s disdain was bottomless. “Thoreau had no deep insight into nature,” said Knight.

Score: an absolute 0.

Fydor Dostoyevsky, Notes from Underground

Dostoyevsky’s novella, written in 1864, is narrated by an unnamed man, angry and misanthropic, who has lived apart from all others for twenty years. The book’s opening lines are: “I am a sick man. I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man.”

Notes from the Underground, says Knight, ideally captures the isolation, anger, and self-loathing that can accompany someone who wants to abandon the world. “Real life oppressed me with its novelty so much that I could hardly breathe,” says the book’s narrator. “It is better to do nothing!”

“I recognize myself in the main character,” admitted Knight.

More profoundly, at the conclusion of the book, the narrator issues a statement of fierce hermit pride: “I have only in my life carried to an extreme what you have not dared to carry halfway, and what’s more, you have taken your cowardice for good sense, and have found comfort in deceiving yourselves. So that perhaps, after all, there is more life in me than in you.”

Underground, says Knight, is a nihilistic masterpiece.

Score: a perfect 10.

http://lithub.com/a-man-who-spent-27-years-alone-in-the-woods-on-the-best-of-hermit-literature/

Clarity:

If a writers thoughts and ideas are misunderstood by the reader–what is the point of reading. Think of how frustrating it is when you read something and later realize that you did not understand what you read. Sometimes this is the writers fault. They were not clear. How can you ensure that your writing is clear and readers understand your ideas?

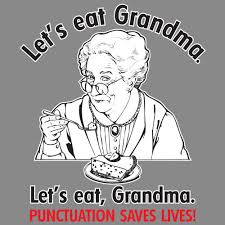

Commas:

You often hear that a comma is a pause in a sentence. This is true, just not the whole story.

Comma Rules:

Rule 1.

Use a comma to separate the elements in a series (three or more things), including the last two. “He hit the ball, dropped the bat, and ran to first base.” You may have learned that the comma before the “and” is unnecessary, which is fine if you’re in control of things. However, there are situations in which, if you don’t use this comma (especially when the list is complex or lengthy), these last two items in the list will try to glom together (like macaroni and cheese). Using a comma between all the items in a series, including the last two, avoids this problem. This last comma—the one between the word “and” and the preceding word—is often called the serial comma or the Oxford comma. In newspaper writing, incidentally, you will seldom find a serial comma, but that is not necessarily a sign that it should be omitted in academic prose.

Rule 2.

Use a comma + a little conjunction (and, but, for, nor, yet, or, so) to connect two independent clauses, as in “He hit the ball well, but he ran toward third base.”

Contending that the coordinating conjunction is adequate separation, some writers will leave out the comma in a sentence with short, balanced independent clauses (such as we see in the example just given). If there is ever any doubt, however, use the comma, as it is always correct in this situation.

One of the most frequent errors in comma usage is the placement of a comma after a coordinating conjunction. We cannot say that the comma will always come before the conjunction and never after, but it would be a rare event, indeed, that we need to follow a coordinating conjunction with a comma. When speaking, we do sometimes pause after the little conjunction, but there is seldom a good reason to put a comma there.

Rule 3.

Use a comma to set off introductory elements, as in “Running toward third base, he suddenly realized how stupid he looked.”

It is permissible to omit the comma after a brief introductory element if the omission does not result in confusion or hesitancy in reading. If there is ever any doubt, use the comma, as it is always correct. If you would like some additional guidelines on using a comma after introductory elements.

Rule 4.

Use a comma to set off parenthetical elements, as in “The Founders Bridge, which spans the Connecticut River, is falling down.” By “parenthetical element,” we mean a part of a sentence that can be removed without changing the essential meaning of that sentence. The parenthetical element is sometimes called “added information.” This is the most difficult rule in punctuation because it is sometimes unclear what is “added” or “parenthetical” and what is essential to the meaning of a sentence.

- Calhoun’s ambition, to become a goalie in professional soccer, is within his reach.

- Eleanor, his wife of thirty years, suddenly decided to open her own business.

More help on commas:

http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/commas.htm

Active Voice:

The subject performs the action.

Verbs are said to be Active or Passive. (Is this sentence active or passive?)

In the active voice, it is clear who is performing the action.

- The boy fed the dog.

In the active voice, it is unclear who performs the action.

- The dog was fed.

The following sentences are passive?The unidentified victim was apparently struck during the early morning hours.

- The aurora borealis can be observed in the early morning hours.

- The unidentified victim was apparently struck during the early morning hours.

Here they are written in the active voice:

- Tourists can see the aurora borealisin the early morning hours.

- An assailant struck the victim during the early morning hours.

However:

The passive voice is especially helpful (and even regarded as mandatory) in scientific or technical writing or lab reports, where the actor is not really important but the process or principle being described is of ultimate importance. Instead of writing “I poured 20 cc of acid into the beaker,” we would write “Twenty cc of acid is/was poured into the beaker.” The passive voice is also useful when describing, say, a mechanical process in which the details of process are much more important than anyone’s taking responsibility for the action: “The first coat of primer paint is applied immediately after the acid rinse.”

A Few Questions for Poetry

Why Poetry? Well, yes. Most books of poetry sell a couple of thousand copies, at best. So in a quantitative sense, what’s the point of supporting it? With dollars or sense? Would we make the same argument for investing in an endangered species? Like the great Indian bustard, one of the heaviest flying birds, down to a couple of hundred of its kind.

The issue is larger than the number of collections of poetry sold each year. It’s about the language — our language. Is it, too, endangered? If the depleted language of emails and texts and Twitter is any indication, then there’s a case to be made that it might be.

Still, a question I often ask myself is why so many people (and we’re now talking about millions of people) turn to poetry for all important rites of passage — weddings, funerals, toasts, tragedies, eulogies, birthdays. . . . Why? Because the language of poetry avoids the quotidian — but the best poetry simultaneously celebrates the quotidian. Language that’s focused in such a way that true meaning and emotion is redolent in the air. The poet W.S. Merwin once said: “Poetry addresses individuals in their most intimate, private, frightened and elated moments . . . because it comes closer than any other art form to addressing what cannot be said. In expressing the inexpressible, poetry remains close to the origins of language.”

Why poetry? I sent out a few emails to see what various people had to say. The poet Louise Glück, on the subject of book sales, wrote back, “The books may not sell, but neither are they given away or thrown away. They tend, more than other books, to fall apart in their owners’ hands. Not I suppose good news in a culture and economy built on obsolescence. But for a book to be loved this way and turned to this way for consolation and intense renewable excitement seems to me a marvel.”

The Greek poet Yiannis Ritsos, jailed for political reasons, wrote his poems on cigarette papers while in prison, stuffed them into the lining of his jacket and, when he was released, walked out wearing his collected poems. They were mostly short.

The Ukrainian poet Irina Ratushinskaya, while in prison, wrote her poems on bars of soap. When she had them memorized, she washed them away.

The novelist Richard Ford differed from the poets in his take: “The question ‘Why poetry?’ isn’t asking what makes poetry unique among art forms; poetry may indeed share its origins with other forms of privileged utterance. A somewhat more interesting question would be: “What is the nature of experience, and especially the experience of using language, that calls poetic utterance into existence? What is there about experience that’s unutterable?” You can’t generalize very usefully about poetry; you can’t reduce its nature down to a kernel that underlies all its various incarnations. I guess my internal conversation suggests that if you can’t successfully answer the question of “Why poetry?,” can’t reduce it in the way I think you can’t, then maybe that’s the strongest evidence that poetry’s doing its job; it’s creating an essential need and then satisfying it.”

When you’re looking for a poem to read at a memorial service, what is it you’re looking for? And why are you looking for a poem? Do you imagine that it is in poetry that you’ll find something you could not have said yourself? And when you find the right poem, what have you discovered? What do you hear? What’s been said? And what do you imagine the mourners are going to hear?

Why read poetry? Emily Dickinson wrote: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?”

Again, why poetry? I wrote the poet Robert Hass. His response: “ ‘Paradise Lost’ was printed in an edition of no more than 1,500 copies and transformed the English language. Took a while. Wordsworth had new ideas about nature: Thoreau read Wordsworth, Muir read Thoreau, Teddy Roosevelt read Muir, and we got a lot of national parks. Took a century. What poetry gives us is an archive, the fullest existent archive of what human beings have thought and felt by the kind of artists who loved language in a way that allowed them to labor over how you make a music of words to render experience exactly and fully.”

So to the question at hand: Why support poetry? Those of us who engage in the publication and sustenance of the written word do so to insure that language for our future generations remains intact, powerful and ultimately renewed, capable of its role during times of crisis and celebration.

Wallace Stevens wrote that the poet’s function was “to help people live their lives.” And because he was a financial guy as well as a poet, he wrote, “Money is a kind of poetry.” I’d reverse that and say poetry is a kind of currency. As Stevens himself put it, “The imagination is man’s power over nature.”

Assignment:

- Who said? “Poetry addresses individuals in their most intimate, private, frightened and elated moments . . . because it comes closer than any other art form to addressing what cannot be said. In expressing the inexpressible, poetry remains close to the origins of language.”

- What does this statement mean, “poetry remains close to the origins of language”? (Use context clues and prior knowledge to answer this question).

- Why does the author of the article suggest a connection to endangered species? How does this further his argument?

- The author quotes Emily Dickinson,: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?” What does Dickinson mean by this?

Article 1:

You’re Only Human, But Your Kids Could Be So Much More

Have you ever wished that there were something different about yourself? Maybe you imagined yourself taller, thinner, or stronger? Smarter? More attractive? Healthier?

Or perhaps, as much as you love your children, you wished that there was something different about them. It is not that the love is missing, but it is precisely because you love them that you imagine they would be happier if they were different in some way. It is also possible that some form of genetic disease runs in your family, or a predisposition to cancer, Alzheimer’s, or to some other potentially terrible health problem.

Until recently, you would have been able to do very little, if anything, about these situations, thoughts, and feelings. However, that might soon change. While you might not be able to fundamentally transform yourself or your existing children, in the near future, you just might be able to play God with your own new, little creations. Think of it as a very personal kind of experiment. Technology that is already available today may well make this experimentation possible for anyone who can pay the price to make a new person, only one that is hoped to be “better.”

I mean a designer baby. You would be literally designing and producing a new type of baby via the same sort of technology that is used to make a GM tomato, mouse, or monkey. The baby would be a genetically modified human or, to phrase it in an edgier manner, a GM human.

Paul Knoepfler

About

Dr. Paul Knoepfler (@pknoepfler) is a professor and biomedical scientist at UC Davis whose research interests focus on the epigenomics of cancer and stem cells, with a particular interest in pediatric tumors. He also writes the stem cell research and policy blog, The Niche. This is an excerpt from his new book, GMO Sapiens: The Life-Changing Science of Designer Babies, available on Amazon.

Would it be legal? In some places, yes.

Ethical? Hard to say, but I have my doubts.

Risky? Definitely.

Regardless of such thorny issues, it will be technically feasible to attempt, and you can bet that someone will try to do it in the coming years. The point of my bluntly laying out the incredible possibilities of what designer baby technology might be able to do for you was to illustrate how seductive it will be to many of us.

Should it fail at first, other scientists and doctors might be deterred. On the other hand, some could well see that as an opening to try it too. The technology will eventually become widely available. It might take two, five, or ten years, but it is coming. Should you as a parent do it? Many of us will answer, “yes.”

Playing God via genetically changing human creation is made possible today by the marrying together of two powerful technologies. The first is now an old technique, in vitro fertilization (IVF), which was mastered by Nobel Laureate Robert Edwards and his colleague Patrick Steptoe four decades ago. The second is a new, cutting-edge genetic technology called Crispr-Cas9 that makes it remarkably simple to directly tinker with the human genome (the DNA sequence) of an early embryo. When combined with IVF, these new genetic tools allow scientists to change the DNA, which is the blueprint of a human embryo, when it consists of just one or a few cells.

Your GMO sapiens (a nickname I’ve come up with to describe these still-hypothetical creations) child might have avoided a terrible disease because genetic technology was used to correct a disease-causing mutation in a critical gene. Your baby, and you as its parent, may have literally dodged cystic fibrosis or a mutation in the BRCA1 gene that puts women at elevated risk of breast and ovarian cancer, just to mention a couple of many possible examples. The hypothetical GM baby girl born without a BRCA1 mutation would not only have a different life, but also she would never pass the mutation on to anyone in her future family tree.

When combined with IVF, new genetic tools allow scientists to change DNA, which is the blueprint of a human embryo.

To produce a GMO sapiens baby, you would begin effectively by placing an order for her or him. It would be a team effort between you and the scientists involved. You might say it would “take a village and a lab” to make a GMO sapiens.

In the same way that today you might order a customized pizza with green olives, hold the onions, Italian ham, goat cheese, and a particular sauce, when you design and order your future GMO sapiens baby you could ask for very specific “toppings.” In this case, toppings would mean your choice of unique traits, selected from a menu: green eyes, hold the diseases, Italian person’s gene for lean muscle, fixed lactose intolerance so the designed individual can eat dairy, and a certain blood type.

Does this sound outlandish?

The personal genetics company, 23andMe, has already put together what is essentially a baby genetic predictor tool. For example, the company has specifically written about how one might go about, as a mother, selecting one’s preference for green eyes and for a reduced risk of certain diseases, by screening the sperm of potential donors for these traits.

Another similar effort is underway from a company called GenePeeks, co-founded by Professor Lee Silver of Princeton University, a proponent of human genetic modification. GenePeeks has developed a technology called Matchright. This service, available at some fertility clinics, enables customers to screen sperm from possible donors for how the genomes of those sperm when combined with the customer’s might lead to certain outcomes in possible future children. The search tool looks both for predicted disease risks and also specific traits.

After the design phase, the GM baby-to-be would go through a series of production steps, one or more of which might be completed outside of the womb, in a laboratory. IVF would play an important role.

Since there are now currently scientists trying to produce artificial or laboratory- produced human wombs, it is even formally possible that, at some point in the future, the “production” of GMO sapiens babies could occur entirely outside of the human body.

Human reproduction could become a process nearly entirely independent of people, relying just on our cells. Scientists, once they had our cells, could “take it from there” so to speak. Not only would sex be unnecessary, but there could also be almost no physical parental involvement at all to produce a baby.

At some point in the future, the ‘production’ of GMO sapiens babies could occur entirely outside of the human body.

Becoming a parent could turn into almost an intellectual exercise. A project. Instead of building a model airplane or jigsaw puzzle with your kid as a project, you as a parent would do a model building exercise, where your kid is the project. In place of plastic and glue or puzzle pieces, scientists would team up with you as the parent to make this new GM child, using your cells and genetic fabric as the starting material. The only other things needed from you would be the money to pay for the process and your input into the design of the baby.

Traditionally, to make GM mice, researchers make changes to the genome of mouse embryonic stem cells. These cells, which also can be made in human form in theory from any person, are like powerful shape shifters or “transformers” of the stem cell world. Embryonic stem cells can turn into any cell type in the body and hence can grow into a whole embryo. After genetically modifying the embryonic stem cells, these special cells are then transferred to female mice and develop into mouse embryos that grow into a GM mouse. In principle, this could be done in people too. However, with Crispr-Cas9 technology it could be done even more simply without using embryonic stem cells.

The genetic modification step is most likely to be done in humans, either in the egg prior to fertilization or in the one-cell embryo right after its fertilization, using Crispr-Cas9. It could even be done “earlier” in the human developmental spectrum in special kinds of stem cells that can turn into human sperm and eggs, called primordial germ cells or PGCs. By making gene edits via Crispr-Cas9 in cells or embryos very early in development, all the cells of the resulting GM human body would probably carry the same desired gene edit.

Otherwise, we could end up in a situation where the resulting GM baby’s cells do not all have the same DNA sequence. This is called mosaicism, and it could lead to disease.

When the laboratory work and your final part (having the embryo implanted in your uterus, your partner’s, or that of a surrogate) are all done, the end result would be your GMO sapiens baby. The hope would be that it would be a “better” baby than nature alone would have provided you with.

Clearly “better” is a subjective term and could invoke frightening scenarios, such as eugenics, the idea of producing genetically superior human beings and getting rid of genetically “inferior” ones. In the past, eugenics has led to disasters, such as the forced sterilization of thousands of people that occurred throughout the US.

Powerful new gene-editing and reproductive technologies will not necessarily catalyze eugenics, but there is a risk that that could happen. It is a danger made greater by some people today embracing the idea of a new, benevolent eugenics that is empowered by novel technologies, such as Crispr-Cas9.

I expect that, at first, the focus of heritable human genetic modification will be to design a healthier baby for you and ultimately a healthier adult.

That sounds noble enough. For example, imagine a designer baby who is inherently resistant to a host of particularly nasty bacteria or parasites such as that which causes malaria, or unable to be infected by certain viruses, such as a hepatitis virus, Ebola, or HIV. A GMO sapiens made resistant to viral infection via Crispr technology would be ironic given that bacteria use Crispr to resist viral infection too.

Or maybe the GM baby would have novel brain architecture or an innovative type of neuron, designed so that she or he could never get autism or Alzheimer’s disease. Tinkering with genetics to change the architecture of the human brain, the most complex object known in the universe, would be fraught with danger. You might well end up causing cognitive impairments and brain diseases.

As mentioned above, the most likely first goal will be to create a GM baby that has been corrected for a single, disease-causing genetic mutation. This mutation, often normally passed along by you or your spouse to the child, would otherwise have caused her to be ill or to die. But now your baby would be born without this mutation, as it would have been corrected by gene-editing when she was just an embryo or even earlier in the reproductive cells used to make her.

Maybe at least in the early days of GMO sapiens production, those doctors, scientists and parents involved would avoid the temptation to tinker with “vanity” traits, such as height, musculature, skin or eye color, or even intelligence, pushing your child to score off the charts on an IQ test. They would just stick to making a healthier GM baby.

Although if you paid enough money, perhaps you could make such, “a la carte,” designer selections at certain businesses in some countries. It would cost more. This would be akin to the way you can pay extra for a “vanity” license plate in some countries.

Those advocating for human genetic modification fall in two camps: those who support therapy to prevent serious genetic disease, and those futurists and some transhumanists who are keen to modify the human genome for the “betterment” of humanity. The latter are attracted to the new Crispr-Cas9 technology and appear to support a new, sometimes-called “liberal” eugenics, where the focus is on making people “better” rather than on preventing reproduction of “inferior” people.

Within the former camp, some advocates have succeeded in getting the use of mitochondrial genetic modification technology (also known as “three- person IVF”) in humans legalized in the UK in 2015. Some advocates of three-person IVF argue that it would not lead to genetic modification, but science says otherwise. So proponents of some forms of human genetic modification are not just here today, but are also actively advocating its use now or in the future.

Advocates of making designer babies imagine new realities. For instance, Professor Silver of Princeton, despite advocating for designer babies, also imagines a future reality in which genetic modification technology changes society. In this future, Silver predicts an upper class of the “GenRich,” who are GM people that control society, and a lower class of “naturals” who are not.v In the predicted future of his book, Remaking Eden, Silver’s GenRich become the new glitterati [4]vi:

“(In a few hundred years) the GenRich — who account for 10 per- cent of the American population — (will) all carry synthetic genes… . All aspects of the economy, the media, the entertainment industry, and the knowledge industry (will be) controlled by members of the GenRich class…. Naturals (will) work as low-paid service provid- ers or as laborers… . (Eventually) the GenRich class and the Natural class will become… entirely separate species with no ability to cross- breed, and with as much romantic interest in each other as a current human would have for a chimpanzee…. (I)n a society that values individual freedom above all else, it is hard to find any legitimate basis for restricting the use of reprogenetics…. (T)he use of reprogenetic technologies is inevitable… . There is no doubt about it…whether we like it or not…”

In this future vision, it would appear a kind of Social Darwinism is at work turbocharged by genetics. Silver coined the term “Reprogenetics” to mean the coordinated use of assisted reproductive and genetics technologies to produce genetically enhanced humans. In a newer 2007 edition of his Remaking Eden book, Silver subtitled it, “How Genetic Engineering and Cloning will Transform the American Family.”

So make no mistake, there will be people who will spend large sums of money to not only have a child, but also to make GM children that are better than those of their peers.

What happens to them and to society as a result? If one looks at art and literature, collectively the prediction would be dire. There is a surprisingly long history of fictional works exploring humans hacking into their own creation. Almost without exception, the results imagined are dystopian in nature. Even today, polling suggests people are very concerned with the idea of human genetic modification and cloning.

A significant number of people would not be able to resist that temptation. Amongst those of us who are parents, who does not like to think that their kids are better than average? What if you could almost guarantee that your child would outshine all of the others in the neighborhood? All the kids in the country? Many of us would give in to that temptation.

https://www.wired.com/2015/12/youre-only-human-but-your-kids-could-be-so-much-more/

Article 2:

To return or not: Who should own indigenous art?

The British Museum in London is opening a major new exhibition with a rather interesting subtitle. Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation the most important show ever in the United Kingdom to look at the art and culture of Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, and though the exhibition has a massive 60,000-year timescale, it presents indigenous Australian art as part of a continuous culture. Objects from the museum’s collection, such as a shield taken by Captain Cook from Botany Bay – now the site of Sydney’s airport – will be displaye1d alongside bark painting from West Arnhem Land, placards from recent indigenous protest movements and works of contemporary art that reckon with Australia’s past and future.

After the show closes in August, many of the objects on display will travel to the National Museum of Australia in Canberra – and there, debate is already roiling. Numerous indigenous activists are distressed, not to say furious, that artworks and artefacts they consider rightfully theirs will travel to Canberra only to return to London: “just rubbing salt into the wounds,” as one activist had it. What could have been a celebration has quickly become a major front in the endlessly challenging debate over the repatriation of artworks from museum collections to their place of origin. If, as the British Museum subtitle has it, indigenous cultures form an “enduring civilisation,” then are they the proper guardians of their own heritage?

Repatriating art to indigenous peoples, such as this Aboriginal bark painting at the British Museum, remains controversial (Credit: The Trustees of the British Museum)

‘Who owns culture?’

Indigenous claims to objects in Western museums should be understood separately from similar claims on behalf of nation states. The British Museum, of course, knows all about the latter: its prized Elgin Marbles, acquired (or looted?) in the early 19th Century, have been claimed by Greece since 1925. No country has been more forceful in its claims to cultural patrimony in recent years than Turkey, whose culture ministry has laid claims to Byzantine artworks made millennia before the establishment of the Turkish republic, and blocked loans to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Louvre and the Pergamon. Such nationalistic muscle-flexing not only rests on sometimes dubious historical premises, but also on a myopic understanding of culture itself, which has never confined itself to national limits. So to the question ‘Who owns culture?’ we can confidently assert the truth of one response: not the nation state. Cultures do not line up with the boundaries on maps.

The Elgin Marbles, taken from the Parthenon in Athens two centuries ago, remain at the British Museum despite Greece’s demands that they be returned (Credit: Getty Images)

But in the case of works of art from indigenous Australia, we are looking at a very different question. Here the petitioners for restitution are not the government of the Commonwealth of Australia, but rather contemporary indigenous communities whose understanding of culture, time and kinship comes into direct conflict with the imperative of the Western museum. This is a much harder, much more fraught debate, raising some of the biggest questions of art and politics: what does it mean to be modern? Does all culture form part of a global heritage that should be available to everyone, even after centuries of war and colonisation? Must everything be presented for universal understanding, or is some knowledge correctly kept secret?

For many indigenous Australians, the objects in the London and Canberra exhibitions are not the material remnants of past lives, but very real connections to their history and their ancestors. They have a point – one that museums have ignored for too long. It remains all too common to see cultural works by indigenous peoples treated as natural history, to be filed away with rocks and bird carcasses, rather than treated as a vital culture in its own right. (When I was a student of art history, I remember the shock of discovering an aboriginal Australian painting in my university’s natural history museum rather than at the art gallery, even though the painting dated from 1988.) As many anthropologists have shown, there is nothing ‘natural’ about the designation of a cultural object as an ‘artefact’ or an ‘artwork’, as living or dead. The distinction is a historically freighted, constantly negotiable dance. In Paris, for example, pre-Columbian sculptures have migrated over and over: from the Louvre and the Musée Guimet in the early-to-mid-19th Century, where they were exhibited as antiquities; to the ethnographic Trocadéro in the late 19th Century, where aesthetics were irrelevant; and now to the Musée du Quai Branly, which proudly calls itself an art museum.

The remains of a child are given a traditional reburial after the Smithsonian Institution in the US gave them back to traditional owners (Credit: Getty Images)

What should be restituted? Some cases are clear – notably the case of human remains, which were acquired (or stolen) by Western museums as recently as the mid-20th Century and have very rarely served any scientific or historical purpose. Indigenous peoples have rightly campaigned for the return of these remains, and they have had success. In 2010, the Smithsonian in Washington returned the skeletons of more than 60 people from Arnhem Land in Australia’s Northern Territory, all of which were less than 120 years old. In 2013, the Charité hospital in Berlin made similar repatriations to Australian and Torres Straits populations. These are excellent examples of museums respecting the claims of indigenous peoples and righting past wrongs.

Toward a solution

The case of sacred objects is trickier, and perhaps irresolvable. The idea of the ‘universal museum’, for all its Enlightenment virtues and educational potential, is at its core a Western imperial project, and museums that acquired sacred objects in earlier times absolutely must rethink their display, their function and their narrative. This can only be done along with native populations; the Association of Art Museum Directors, the main museum authority in the United States, instructs its members to work with indigenous groups on display and interpretation.

Yet the legitimate injustices of colonisation cannot be undone even if every object in every museum were restituted. What’s more, the very recourse to a terminology of “ownership” imbues ancient cultural questions with modern, capitalist practices – suddenly, culture sounds not so much like a living thing, but rather a lot like a copyright. The most extreme claims of cultural ownership can turn so absolute that it’s hard to account for them. Some indigenous people, for example, believe that a representation of an ancestor (such as in a photograph or a recording) embodies its subject – and thus no such documentation should be permitted. Important though it is to understand this cultural sensitivity, there’s just no way to undo the entirety of modern anthropology and museology. Some compromise has to be found.

The goal must be for museums to honour and nurture the cultural heritage of indigenous peoples and at the same time to foster the understanding and the cross-cultural communication that pluralist liberal democracy requires. This can be done – and Australian institutions in particular have shown a way forward. Since the 1970s, the Australian Museum in Sydney has collaborated with indigenous communities to improve its interpretive displays and to understand the sacred character of some objects. The museum has an outreach unit that trains indigenous people in New South Wales with curatorial and conservation skills. And it now collects contemporary indigenous artworks, whether in traditional or in ‘Western’ media, to counteract the damaging falsehood of static culture.

One of the items showing at the British Museum is this Aboriginal shield collected by James Cook in 1770 (Credit: The Trustees of the British Museum)

We cannot unwind the universal museum, but we can build a better one – one where indigenous peoples participate at every step of the way in the display, interpretation and exhibition of their heritage. In this way, indigenous people can use the universal museum to rectify historical inequities, rather than merely let the museum promulgate the sins of the past. Exhibitions of cultural objects can provide evidence for indigenous claims to land, for example. Indigenous collaborations with museums can lead to more heterogeneous understandings of national or regional culture, and thus to fairer laws and fairer representations. Museums, even the British Museum, should not be seen as old imperial villains, but as living and mutable enterprises that can transform our understanding of others and of ourselves. That would benefit not only indigenous peoples, but all of us who want to build a more just and more cosmopolitan future.

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20150421-who-should-own-indigenous-art

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Assignment:

Write a multiple paragraph response that introduces the topic, makes a counterclaim, and has a rebuttal.

Remember to use I.C.E

Compose your response in a google doc, print it, and hand it in at the end of the period.

If you finish early or wish to be more thorough in your response, click the blue hyperlinks in the article and research their content (bonus points for this).

First Five–Quick Write:

Name one thing you will do, or one strategy you will use during the SBAC, to ensure your success.

_____________________________________________________________

We have studied these three types of writing through the year. Now we will review and test what we know.

Narrative

Expository

Argumentative

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Narrative Writing:

A piece of narrative writing tells a story. It often includes personal anecdotes which create an emotional response in the reader. Students are often asked to produce narrative samples and essays at the beginning of the school year. How often have you had an assignment where you were asked to write about something you did over the summer. What you wrote for that assignment was a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end.

Example:

Some people express themselves through beautiful art; others are masters of the page and speak silently through writing. I, on the other hand, express myself with the greatest instrument I have, my voice. I make my living by speaking to groups large and small. Nothing gives me more satisfaction than public speaking, and my interest in public speaking began when I was quite young.

At age eight I realized that I belonged in front of an audience. I started giving demonstrations and speeches in local county 4-H competitions until I was eligible to participate in state competitions. I won every state competition that I entered.

Expository Writing:

This type of writing explains, describes, give information, or informs the reader.

Example:

People often think all planets are alike, but there are actually three types of planets in the solar system. The terrestrial planets are made of rock and metal and are closest to the sun. These include the midsize planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. They rotate slowly and don’t have many moons. Farther from the sun are the planets called gas giants, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. They are called gas giants because they are formed from gases such as hydrogen and helium. Gas giants rotate fast and have many moons. Finally, planetoids are objects made up of rock and ice and are too small to be true “planets.” Planetoids sometimes even get pulled into a planet’s gravitational field and become moons themselves. Whether they are terrestrials, gas giants, or planetoids, the planets in the solar system are fascinating.

Argumentative Writing:

You are most failure with argumentative writing (we’ve been doing it everyday, all year). Sometimes it is called persuasive writing. Argumentative writing involves making a claim and providing evidence for that claim. Remember out thesis construction:

Thesis = Topic + Claim + Evidence

_____________________________________________________________

Assignment

Station one: Narrative Writing — Each person in the group will write one paragraph paragraph about a difficulty they experienced and overcame this year.

Andrea, Jesus, Saybeth, Adam, Jasmin

Station Two: Expository Writing — Each person in the group will write one paragraph paragraph explaining how to do something or describe how something works. ( how to post a video to YouTube, three ways you can tweeze your eyebrows etc. ).

Sebastian, Lauren, Breanna, Ali

Station Three: Argumentative Writing — Each person in the group will write one paragraph paragraph that makes an argument with a thesis in the last sentence. ( Edward Snowden should turn himself in because it will discourage leakers ).

Uriah, Daniella, Daisy, Isaac, Giovanni

We will share our writing afterward–please do not write anything too personal that will prohibit your desire to share with the class.